Sam Gregory is Program Director of WITNESS. We talked to Sam about the development and challenges of new ways to create mis- and disinformation, specifically those making use of artificial intelligence. We discussed the impact of shallow- and deepfakes, and what the essential questions are with development of tools for detection of such synthetic media.

The following has been edited and condensed.

Sam, what is your definition of a deepfake?

I use a broad definition of a deepfake. I use the phrase synthetic media to describe the whole range of ways in which you can manipulate audio or video with artificial intelligence.

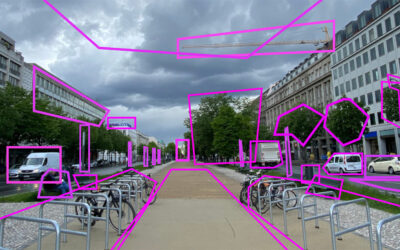

We look at threats and in our search for solutions we look at how you can change audio, how you can change faces and how you can change scenes by for example removing objects or adding objects more seamlessly.

What is the difference to shallowfakes?

We use the phrase shallowfake in contrast to deepfake to describe what we have seen for the past decade at scale, which is people primarily miscontextualizing videos like claiming a video is from one place when it is actually from another place. Or claiming it is from one date when it is actually from another date. Also when people do deceptive edits of videos or do things you can do in a standard editing process, like slowing down a video, we call it a shallowfake.

The impact can be exactly the same but I think it’s helpful to understand that deepfakes can create these incredibly realistic versions of things that you haven’t been able to do with shallowfakes. For example, the ability to make someone look like they’re saying something or to make someone’s face appear to do or say something that they didn’t do. Or the really seamless and much easier ability to edit within a scene. All are characteristics of what we can do with synthetic media.

We did a series of threat modeling and solution prioritization workshops globally. In Europe, US, Brazil, Sub-Sahara Africa, South and Southeast Asia people keep on saying, we have to view both types of fakes as a continuum and we have to be looking at solutions across it. And also we need to really think about the wording we use because it may not make that much difference to an ordinary person who is receiving a WhatsApp message whether it is a shallowfake or a deepfake. It matters, whether it’s true or false.

Where do you encounter synthetic media the most at the moment?

Indisputably the greatest range of malicious synthetic media is targeting women. We know that from the research that has been done by organizations like Sensity. We have to remember that synthetic media is a category in the non-malicious, but potentially malicious usages. There is an explosion of apps that enable very simple creation of deepfakes. We are seeing deepfakes starting to emerge on those parody lines, a kind of an appropriation of images. And, at what time does software become readily available to lots of people to do moderately good deepfakes that could be used in satire, which is a positive usage but can also be used in gender-based violence?

Where is the highest impact of deepfakes at the moment?

It is on the individual level. In terms of impact on individual women and their ability to participate in the public sphere, related to the increasing patterns of online and offline harassment that journalists and public figures face.

Four threat areas were identified in our meetings with journalists, civic activists, movement leaders and fact-checkers that they were really concerned about in each region.

- The Liars dividend, which is the idea that you can claim something is false when it is actually true which forces people to prove that it is true. This happens particularly in places where there is no strong established media. The ability to just call out everything as false benefits the powerful, not the weak.

- There is no media forensics capacity amongst most journalists and certainly no advanced media forensics capacity.

- Targeting of journalists and civic leaders using gender-based violence, as well as other types of accusations of corruption or drunkenness.

- Emphasis on threats from domestic actors. In South Africa we learned that the government is using facial recognition, harassing movement leaders or activists.

These threats have to be kept in mind with the development of tools for detection. Are they going to be available to a community media outlet in the favelas in Rio facing a whole range of misinformation? Are they going to be available to human rights groups in Cambodia who know the government is against them? We have to understand that they cannot trust a platform like Facebook to be their ally.

Can be synthetic media used as an opportunity as well?

I come from a creative background. At WITNESS the center of our work is the democratization of video, the ability to film and edit. Clearly these are potential areas that are being explored commercially to create video without requiring so much investment.

I think if we do not have conversations about how we are going to find structured ways to respond to malicious usages, I see positive usage of these technologies being outweighed by the malicious usage. And I think there is a little bit too much of a „it will all work itself out” approach being described by many of the people in this space.

We need to look closely at what we expect of the people who develop these technologies: Are they making sure that they include a watermark? That they have a provenance tree that can show the original? Are they thinking about consent from the start?

Although I enjoy playing with apps that use these types of tools, I don’t want to deny that I think 99% of the usage of these are malicious.

We have to recognize that the malicious part of this can be highly damaging to individuals and highly disruptive to the information ecosystem.