Sam Gregory is Program Director of WITNESS, an organisation that works with people who use video to document human rights issues. WITNESS focuses on how people create trustworthy information that can expose abuses and address injustices. How is that connected to deepfakes?

In-Depth Interview – Sam Gregory

In-Depth Interview – Sam Gregory

Sam Gregory is Program Director of WITNESS, an organisation that works with people who use video to document human rights issues. WITNESS focuses on how people create trustworthy information that can expose abuses and address injustices. How is that connected to deepfakes?

Sam Gregory is Program Director of WITNESS. We talked to Sam about the development and challenges of new ways to create mis- and disinformation, specifically those making use of artificial intelligence. We discussed the impact of shallow- and deepfakes, and what the essential questions are with development of tools for detection of such synthetic media.

The following has been edited and condensed.

Sam, what is your definition of a deepfake?

I use a broad definition of a deepfake. I use the phrase synthetic media to describe the whole range of ways in which you can manipulate audio or video with artificial intelligence.

We look at threats and in our search for solutions we look at how you can change audio, how you can change faces and how you can change scenes by for example removing objects or adding objects more seamlessly.

What is the difference to shallowfakes?

We use the phrase shallowfake in contrast to deepfake to describe what we have seen for the past decade at scale, which is people primarily miscontextualizing videos like claiming a video is from one place when it is actually from another place. Or claiming it is from one date when it is actually from another date. Also when people do deceptive edits of videos or do things you can do in a standard editing process, like slowing down a video, we call it a shallowfake.

The impact can be exactly the same but I think it’s helpful to understand that deepfakes can create these incredibly realistic versions of things that you haven’t been able to do with shallowfakes. For example, the ability to make someone look like they’re saying something or to make someone’s face appear to do or say something that they didn’t do. Or the really seamless and much easier ability to edit within a scene. All are characteristics of what we can do with synthetic media.

We did a series of threat modeling and solution prioritization workshops globally. In Europe, US, Brazil, Sub-Sahara Africa, South and Southeast Asia people keep on saying, we have to view both types of fakes as a continuum and we have to be looking at solutions across it. And also we need to really think about the wording we use because it may not make that much difference to an ordinary person who is receiving a WhatsApp message whether it is a shallowfake or a deepfake. It matters, whether it’s true or false.

Where do you encounter synthetic media the most at the moment?

Indisputably the greatest range of malicious synthetic media is targeting women. We know that from the research that has been done by organizations like Sensity. We have to remember that synthetic media is a category in the non-malicious, but potentially malicious usages. There is an explosion of apps that enable very simple creation of deepfakes. We are seeing deepfakes starting to emerge on those parody lines, a kind of an appropriation of images. And, at what time does software become readily available to lots of people to do moderately good deepfakes that could be used in satire, which is a positive usage but can also be used in gender-based violence?

Where is the highest impact of deepfakes at the moment?

It is on the individual level. In terms of impact on individual women and their ability to participate in the public sphere, related to the increasing patterns of online and offline harassment that journalists and public figures face.

Four threat areas were identified in our meetings with journalists, civic activists, movement leaders and fact-checkers that they were really concerned about in each region.

- The Liars dividend, which is the idea that you can claim something is false when it is actually true which forces people to prove that it is true. This happens particularly in places where there is no strong established media. The ability to just call out everything as false benefits the powerful, not the weak.

- There is no media forensics capacity amongst most journalists and certainly no advanced media forensics capacity.

- Targeting of journalists and civic leaders using gender-based violence, as well as other types of accusations of corruption or drunkenness.

- Emphasis on threats from domestic actors. In South Africa we learned that the government is using facial recognition, harassing movement leaders or activists.

These threats have to be kept in mind with the development of tools for detection. Are they going to be available to a community media outlet in the favelas in Rio facing a whole range of misinformation? Are they going to be available to human rights groups in Cambodia who know the government is against them? We have to understand that they cannot trust a platform like Facebook to be their ally.

Can be synthetic media used as an opportunity as well?

I come from a creative background. At WITNESS the center of our work is the democratization of video, the ability to film and edit. Clearly these are potential areas that are being explored commercially to create video without requiring so much investment.

I think if we do not have conversations about how we are going to find structured ways to respond to malicious usages, I see positive usage of these technologies being outweighed by the malicious usage. And I think there is a little bit too much of a „it will all work itself out” approach being described by many of the people in this space.

We need to look closely at what we expect of the people who develop these technologies: Are they making sure that they include a watermark? That they have a provenance tree that can show the original? Are they thinking about consent from the start?

Although I enjoy playing with apps that use these types of tools, I don’t want to deny that I think 99% of the usage of these are malicious.

We have to recognize that the malicious part of this can be highly damaging to individuals and highly disruptive to the information ecosystem.

Should we use synthetic media in satire for media literacy?

We have been running a series of webtalks called deepfakery . One of the main questions is, what are the boundaries around satire? Satire is an incredibly powerful weapon of the weak against the powerful. So for example, in the US we see the circulation of shallowfakes and memes made on sites that say very clearly on the top that this is satire. But of course no one ever sees that original site. They just see the content retweeted by President Trump in which case it looks like it is a real claim.

So satire is playing both ways. I do think the value of satire is to help people understand the existence of this and to push them to sort of responsibly question their reaction to video.

I think the key question in the media literacy discussion is: how do we get people to pause? Not to dismiss everything but to give them the tools to question things. Give them the tools to be able to pause emotionally before they share.

From a technology point of view, what are we still missing to detect synthetic media?

Synthesis of really good synthetic media is still hard. So synthesizing a really good faceswap, or a convincing scene is still hard. What is getting easier is the ability to use apps to create something that is impactful but perhaps not believable. I think sometimes people over assume how easy it is to create a deepfake.

We’re not actually surrounded by convincing deepfakes at this point.

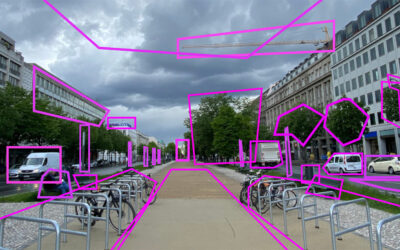

A lot of our work has been thinking about detection and authentication. How do you spot evidence of media manipulation which could be detection of a deepfake or detection of a shallowfake? How to spot that a video has been miscontextualized and there is an original or an earlier version that has different edits? Then authentication, how do we trace a video over time to see it’s manipulations.

At the moment the detection of synthetic media is, and this is the nature of the technology, an arms race between the people who will develop the detection tool and those who will use it to test and enhance their new synthesis tool. The results of detection tools are getting better but they are not at the level that you could do it at scale.

The meta question for us on detection is actually who to make this accessible to. If it is only the BBC, Deutsche Welle, France 24 and New York Times, that leaves out 90% of the world as well as ordinary people who may be targeted by this in an incredibly damaging way.

Do all journalists need to be trained in using advanced forensic technology?

One of the things we have learned as we have been working on deepfakes is that we shouldn’t exclusively focus on media forensics. I think it is important to build the media forensic skills of journalists and it is a capacity gap for almost every journalist to do any kind of media forensics with existing content. I do not think we can expect that every journalist will have that skill set. We also need to consider how we invest in e.g. regional hubs of expertise.

The bigger backdrop is that we need to build a stronger set of OSINT skills in journalism. We need to be careful not to turn this purely into a technical question around media forensics at a deep level because it is a complicated and specialist skill set.

We identified a range of areas that need to be addressed to develop tools that plug into journalistic workflows. For example that journalists are not going to rely on tools easily. They do not need just a confidence number, they need software to explain why it is coming up with this result. So, I think we need a constant interchange between journalists and researchers and tools developers and the platforms to say what the tools are that we really need as this gets more pervasive. And we need tools that potentially provide information to consumers and community leader level activists to help them do the kind of rapid debunking and rapid challenging of the kind of digital wildfire of rumors that journalists frankly often do not get too. Often community leaders are talking about things that circulate very rapidly in a Favela or a Township and journalists never get to them in a timely way. So we need to focus on journalists, but also on community leaders.

What are your three tips for consumers to deal with synthetic media?

- Pause before you share the content.

- Consider the intention of why people are trying to encourage you to share it.

- To take an emotional pause when consuming media trying to understand the context of it is supported by a range of tools like the SIFT methodology or the Sheep Acronym.

I don’t think it is a good idea to encourage people to think that they can spot deepfakes.

The clearest and most consistent demand we heard primarily from journalists and fact checkers is to show them if this is a mis-contextualized video so that they can then just clearly say, no this video is from 2010 and not from 2020.

Therefore reverse video search or finding similar videos is pretty important because that shallowfake problem remains the most predominant.

Many thanks Sam! Here’s the ‘Ticks or it didn’t happen‘ report that Sam mentioned. If you are interested to learn more or have questions then please get into contact with us, either via commenting on this article or via our Twitter channel.

We hope you liked it! Happy Digging and keep an eye on our website for future updates!

Don’t forget: be active and responsible in your community – and stay healthy!

Related Content

In-Depth Interview – Sam Gregory

Audio Synthesis, what’s next? – Parallel WaveGan

The Parallel WaveGAN is a neural vocoder producing high quality audio faster than real-time. Are personalized vocoders possible in the near future with this speed of progress?

In-Depth Interview – Jane Lytvynenko

We talked to Jane Lytvynenko, senior reporter with Buzzfeed News, focusing on online mis- and disinformation about how big the synthetic media problem actually is. Jane has three practical tips for us on how to detect deepfakes and how to handle disinformation.